Unveiling Ossabaw’s Secrets

From the 1890’s to the 21st century, Ossabaw Island has revealed to scientists important information on human history, animal behavior, oceanography, and ecological and geological trends.

Twentieth century researchers conducted archeological analysis of Native American communities, studied Ossabaw’s feral pig and donkey populations, and monitored protected species over several decades –loggerhead sea turtles, wood storks, and bald eagles. Much of this species monitoring continues today. Dozens of research paper have been published as a result of these efforts. For 21st century scientists, the Barrier Island Observatory is a network of data sensors that monitors the island’s atmospheric and soil conditions. Internet connectivity transmits the data to off-island researchers and provides a vital global communications link for all who study or create on Ossabaw Island.

Scientific professionals, educators and students interested in study or research on Ossabaw Island are encouraged to submit a proposal form. Click the link below to access the form.

19th & 20th Century Research

The first known scientific research on Ossabaw Island occurred in 1897. Archeologist C.B. Moore investigated the island’s prehistoric Indian burial mounds; the detailed field notes he produced are still used. To read about C.B. Moore, click here.

In the 1930’s, The National Geographic Society came to coastal Georgia to document the coastal estates of Georgia’s Golden Isles. The estate of Dr. Henry Norton Torrey and his wife Nell Ford Torrey on Ossabaw was featured in the 1934 National Geographic magazine article. By the 1970’s, scientists from around the world were exploring the island through the Ossabaw Island Project and the Ossabaw Foundation’s Professional Research programs.

Beginning in the 1960’s, Dr. Eugene Odum, considered by many to be the “father of ecology,” studied the island’s 26,000 acres. Odum, Director of the University of Georgia’s Institute of Ecology, studied the island’s salt marshes and freshwater wetlands. During that same period the Yerkes National Primate Research Center at Emory University conducted ground-breaking chimpanzee research on Ossabaw’s Bear Island. Other scientists conducted in-depth research on Ossabaw’s feral hog and free ranging donkey populations.

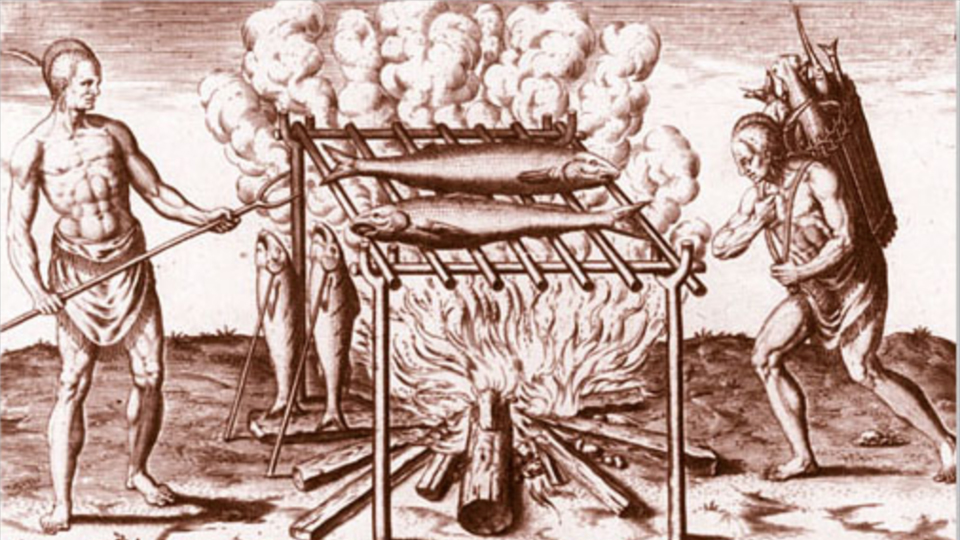

During the 1970’s, archeologists returned to Ossabaw to continue the work begun by C. B. Moore. Their surveying resulted in more than 200 prehistoric Indian sites being mapped and the discovery of a 4000 year old pottery shard which, still today, marks the earliest evidence of human activity on the island.

Since the island’s transfer to state ownership in the late 1970’s, the Georgia Department of Natural Resources (DNR) has implemented management plans based on decades-long research activities. DNR also monitors a number of protected species including the endangered Loggerhead sea turtle, wood storks and American bald eagles. The University of Georgia’s School of Veterinary Medicine has studied Ossabaw Island for over thirty years through its Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study program.

Burial Site Sheds Light on Prehistoric Culture

An excavation in late 2008 of a prehistoric American Indian burial site on Ossabaw Island revealed cremated remains, an unexpected find that offers a glimpse into ancient Indian culture along Georgia’s coast.

State archaeologist David Crass of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources said prehistoric cremations were rare, particularly during the early time in which preliminary evidence suggests this one occurred, possibly 1000 B.C. to A.D. 350. The remains also mark the first cremation uncovered on Ossabaw.

“This interment broadens our knowledge about … the kinds of belief (involving) death within the Woodland Period,” Crass said. “This is not something we have seen before on Ossabaw Island. Similar cremations on St. Catherine’s Island may point to this practice being more wide-spread than we have believed up to now.”

Crass said during this time American Indians in Georgia moved to the coast in the winter for shellfish, then inland in the spring for deer hunting and into uplands in the fall for gathering nuts. “This site may have been a winter season camp,” he said.

Erosion from natural causes exposed the burial on an Ossabaw bluff in mid-2008. Scientists from the DNR Office of the State Archaeologist, the non-profit Lamar Institute and the Georgia Council on American Indian Concerns worked under the council’s direction to excavate the roughly 6- by 6-foot pit. As required by state law, Crass informed the council about the situation and organized the excavation at the group’s request. The work revealed a cremation pit that had been lined with wood and oyster shells. The body had been placed on top of the wood and the contents of the pit burned. The human remains recovered were primarily from extremities, indicating that the deceased had been disinterred after cremation, possibly to be reburied elsewhere. The charcoal will be submitted for carbon 14 dating, but preliminary analysis of the pottery recovered from the pit suggests the cremation may date to the period from 1000 B.C. to A.D. 350. A ground-penetrating radar survey showed many prehistoric American Indian features in the general area, Crass said. The bluff apparently had long been a focal point of prehistoric human activity.

After analysis, the remains will be reinterred in a secure location under the auspices of the Council on American Indian Concerns. Crass expects the carbon 14 dating results and details on the radar survey in 2009.

Source: Georgia Department of Natural Resources