Gullah-Geechee Landscapes on Ossabaw Island

by Nicholas Honerkamp, Meredith Gilligan, Taylor Maxie

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga

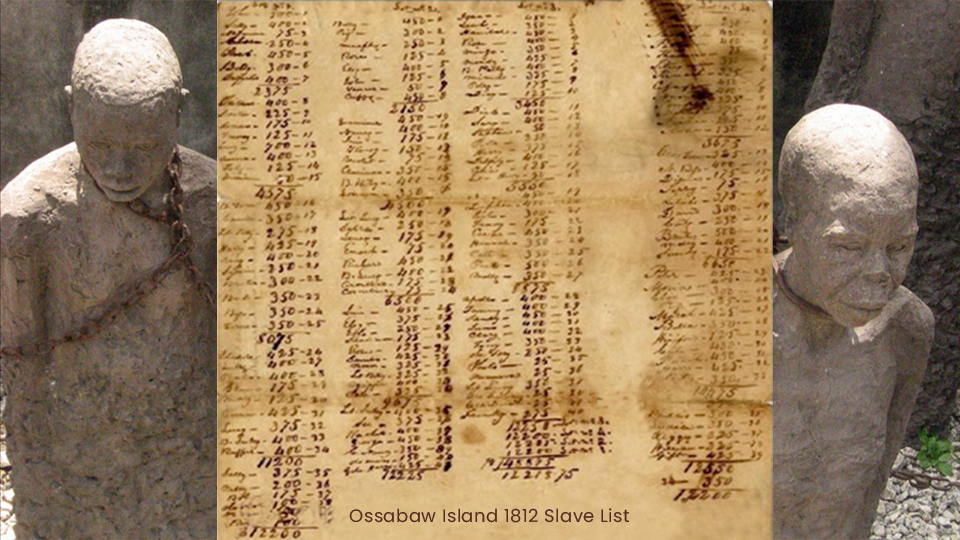

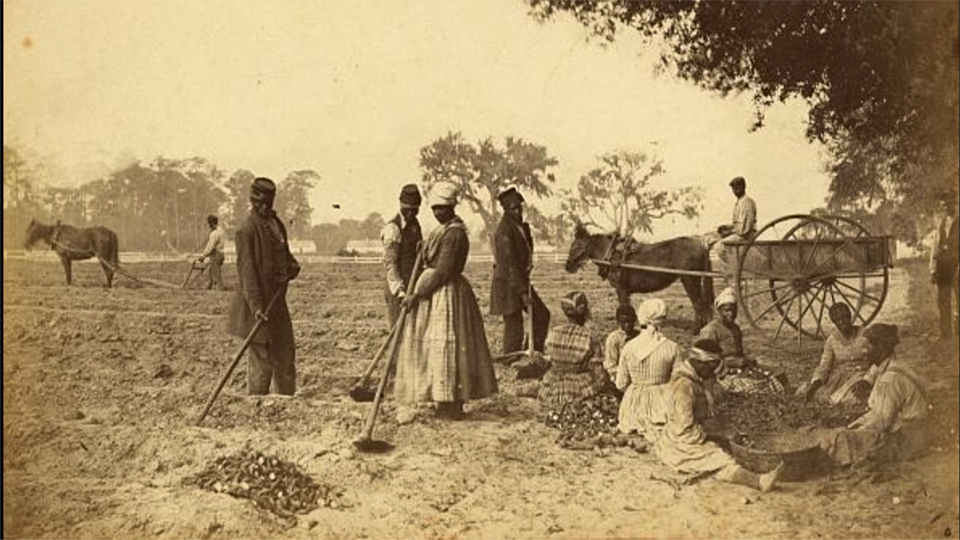

Ossabaw Island was settled relatively early by European and African groups: John Morel, Sr., established the island’s first plantation on the North End by 1763. Indigo, Sea Island cotton, and livestock headed the list of plantation products that were originally grown for Morel by his Not End slaves. By the Revolutionary War, Morel was a prosperous planter, owning several plantations and numerous slaves. Besides growing crops, the slaves harvested timber and engaged in maritime vessel construction. Morel was also a successful Savannah-based merchant for luxury goods. While his high-end retailing and his Ossabaw plantation appear to have thrived, by 1774 Morel had moved his residence to the mainland where he died in 1776.

Indigo Plantation Labor

Unfortunately, determining which of the slaves who lived and worked on Ossabaw rather than on a mainland plantation is vexing at best since information specifying where they worked is non existent. While specific slave demographic data is missing for the North End, Dan Elliott (2007) located several newspaper advertisements for runaway morel slaves, and the relatively high number of these unmistakable examples of resistance suggests an unusually harsh environment for the enslaved Africans. A contributing factor may have been the primary crop that was originally grown there; indigo. This complex, messy and labor-intensive crop was often lethal to its labor force, thanks to the noxious fumes associated with processing indigo with lye. An early 19th century account of the production process stated: “…and such is the effect of the indigo upon the lungs of the laborers, that they never live over seven years” (Roberts 2001:28).

Planter-Slave Relationship on Ossabaw Island

One newspaper notice found by Elliot describes a group of 10 men, women, and children who used a 20-foot-long sloop to make good their 1781 escape. Three of the adults had previously escaped from another Morel plantation on the mainland and, ironically, had been banished to Ossabaw so as to discourage future escape attempts! From the frequency of redundant escapee names, it appears that some slaves were serial fugitives, particularly an individual named Titus, who successfully escaped escaped in the late 1780s and seemingly made it his business to assist other Morel slaves to do the same. In all, Elliott documents a minimum of 30 slaves who escaped or attempted escape from the North End. Interestingly, and perhaps paradoxically, he also indicates a small number of slaves who were manumitted by the Morels. Suffice it to say that the planter-slave relationship at Ossabaw seems to have been complex.

Freedmen

1865 to 1867

After John Morel, Sr.’s death the plantation experienced a checkered economic history under the Morel family’s ownership. Slaves associated with Morel plantations decreased over time, and the Morel family abandoned the North End by 1861.

Thanks to the implementation Sherman’s Field Order 15, 78 Freedmen claimed 2,000 acres on Ossabaw by 1865; Elliot (2007:44) identifies the freeman John Paul family as residing at the North End in that year. Tunis CG. Campbell, a minister in charge of Sea Island resettlement, aided Ossabaw’s freeman in building a school.

However, Field Order 15 was rescinded by 1867 and the Morels soon re-possessed their holdings.

1881 to 1898

Move to Pin Point

Following the Civil War, many of the Freedmen who inhabited Ossabaw Island lived there for several decades as tenants or workers for the white property owners. The population of the island in the 1880 census numbered 180 persons and most, if not all, were of African-American descent. The scarcity of whites on the island allowed these Gullah-Geechee residents to live relatively unmolested lives there, although their numbers declined over time.

At least one Geechee church existed on Ossabaw by the 1870s. With a congregation of 68 souls, the Hinder Me Not Baptist Church was relocated to the mainland at Pin Point sometime before 1900. Its original location and the slave and Freedman cemetery or cemeteries on Ossabaw are unknown.

Between 1881 and 1898, when several hurricanes ravaged the coast, most Geechee-Gullah inhabitants moved to the mainland. The few who remained were primarily in the employ of the Island’s absentee landowners or were sharecroppers. A session of wealthy white landowners used the island primarily as a private hunting preserve.

Present Day

Over the past two decades, The Ossabaw Island Foundation, along with educational institutions and the Pin Point Community, have worked diligently to research, document and preserve Ossabaw Island’s African American culture and history.

Through the Ossabaw Island Foundation, descendants of the Island’s Gullah-Geechee community visit the island to explore the island touch base with their family histories and share stories.